Shanta wonders how to respond to the political market failures that lead a majority of voters in very poor countries to not vote for policies that would benefit the majority. Option 1 is to favor policies that rely on politicians as little as possible, though “they don’t always work. An attempt to reduce health-worker absenteeism in India by introducing time-date stamp machines to record attendance failed when, the night before the program was to start, all the machines were vandalized.” The other path, of course, is to improve the system, but since we usually need people who benefit from the current system in order to establish the better one, this may be more difficult than he lets on.

Speaking of political market failures, which of these is the bigger failure, this one in the US, this one in Tunisia, or this one in Canada?

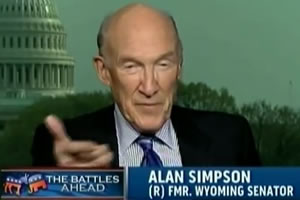

1) "According to former Senator Alan Simpson not only did he not familiarize himself with the relevant life expectancy data during his many years in the Senate, he’s never once brought it up during his months of work on a commission specifically charged with re-evaluating America’s retirement programs."

2) "Landowners are trying to build as fast as they can while the building codes go unenforced. When a new government comes in this summer, everyone thinks that window of opportunity will close."

3) "Ruth-Ellen Brosseau [is] the MP-elect for a French-speaking district outside Montreal. Brosseau doesn’t speak French. She doesn’t even live in Québec. Nor did she make any effort to actually campaign in support of her own election. Apparently, she never even set foot in the district or made a single public statement during the six-week election campaign [and was on vacation in Las Vegas during the campaign]. Nevertheless, she defeated the incumbent Bloc MP by more than 10 percentage points." In fact, on May 7 she finally broke her silence to speak with the press and said that, while she had never been to her district, she "plans to go soon," adding “I’m really excited to come, I’ve heard it’s a beautiful place.”

The Mises Institute kindly tells us how the third could happen:

It doesn’t take a political strategist to figure out what happened here. Like many political parties, the NDP wanted to field as many candidates as they could throughout Canada. They didn’t expect to win many seats in Québec given the Bloc’s previous popularity (and the lack of any prior support for the NDP). So they asked Ms. Brosseau, no doubt a party loyalist who had a friend somewhere in the campaign’s high command, to allow her name to stand on the ballot. And then Québec voters went nuts and staged a mass defection from the Bloc to the NDP — the one federalist party that hadn’t pissed them off in the past.

That the NDP indiscriminately fielded candidates without vetting them — or having them run even a barebones campaign — is also a consequence of the Canadian election system’s perverse economic incentives. Political parties receive a $2-per-vote subsidy from the federal treasury based on the results of the previous election. So even if the NDP fields a token candidate who gets 1,000 votes in a safe Conservative district, that’s $2,000 more for the party treasury next time around. As always, when the government subsidizes something, you get quantity over qualty [sic].

No comments:

Post a Comment