A change in the interest rate or tax rate is not the same as a shock, in the sense that at least part of the change might be expected. This is a longstanding insight in the context of the stock market. A firm which reports improved earnings and higher forecasted profits might still encounter a drop in its share price, simply because the market expected an even stronger report.The World Food Prize - which we consider the Nobel for food, agriculture, and nutrition - went to the presidents of Brazil (Lula da Silva) and Ghana (John Agyekum Kufuor) who successfully reduced hunger and undernutrition in their countries by massive amounts. In my own research, both scored very highly for their political will to reduce hunger also, so I'm glad to see that verified by other measures. They'll be speaking at the conference tonight, I believe.

The chemistry and physics prizes both went to people who, in the last 30 years, overturned our understandings. The chemistry laureate (Dan Schechtman) discovered a form of "quasicrystal" in the mid-80s that had a structure we believed was impossible. Having found it really exists, however, we have been able to improve our non-stick pans (among many other things) by manufacturing these quasicrystals. At the time, though, he was laughed to scorn and thrown out of his research group for persisting in believing something scientists "knew" was impossible.

In physics, the laureates (Saul Perlmutter, Brian P. Schmidt, and Adam G. Riess) changed our best guess about how the universe expands. We had known the universe is expanding, but the dominant paradigm was that it was expanding more and more slowly. They showed that it is in fact growing at a faster rate than before.

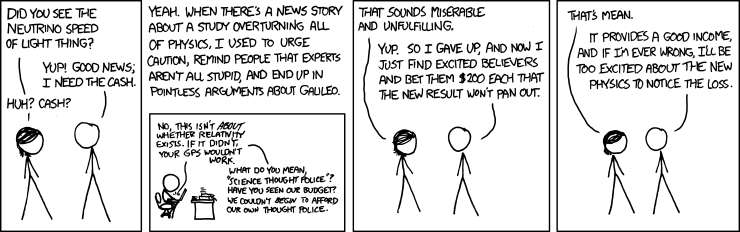

Both of these prizes, I should point out, both show how the scientific method eventually corrects misperceptions and that we need to be much more humble about what science tells us. Within 20-30 years we may believe things that are completely different from what we believe now. Science is not exact. It is a process of falsification and the things we believe today are merely those we have not yet falsified. Be more humble when you place your faith in science. (Although, do remember to also be sceptical of new studies too:)

No comments:

Post a Comment