But you ask me why other people don't think the way we do, so this is my attempt to give them a fair shake. I actually had to write a paper once on why some people don't support free trade. The short answers are:

- They don't understand free trade. (#1 reason)

- If they understand free trade is good in general, they may not understand what is really meant by "strong" and "weak" currencies or where trade deficits come from. Those we aren't going to cover in micro principles, but they are important parts of understanding free trade.

- They understand that free trade maximizes total utility, but they are concerned about the distribution of the gains and losses. The ethics behind free trade says that the winners could compensate the losers of a change to free trade, but in general they don't - no more than the winners of protection compensate the losers. If you think most of the losses will hit poor people, there is a reasonable ethical ground for wanting to discourage some trade. Now, we could do things better by still allowing trade and doing something else for poor people, but I can understand the argument anyway. This analysis also usually forgets the much poorer people in another country who gain a job that allows them to survive.

- As a rich country, the US can afford little luxuries like high labor and environmental standards that other countries may not. If you are categorically opposed to child labor in sweatshops or unsustainable fishing and air pollution, you might be concerned about more production moving to areas that don't regulate those items as much. There are arguments that go the other way, but again I can understand why someone who places a high value on the environment might not want production to move away from where we can regulate it.

- If there are any externalities (like air pollution) you can also make the argument that the market price does not reflect the true costs and benefits, so markets will oversupply goods. Moving to somewhere that has a larger disparity between private and social costs (either because the firm will be more polluting there and increase the social costs, or different regulations lower private costs, or whatnot) will tend to exacerbate that problem.

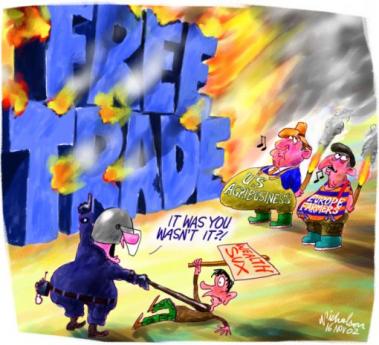

- It's a colonialist/egalitarian thing. If the rules of free trade agreements favor countries that are already wealthy (and they do), it is possible for a government to harm its citizens by opening to freer trade. The rules of accession to the WTO, for instance, allow current members to exact concessions from new members that either nullify WTO rules (WTO-) or require higher standards for entry (WTO+) so that the "rules-based" system becomes a power-based system. For egalitarian reasons, someone might not like that arrangement even if they like free trade per se.

Now these aren't actually the arguments most people make. But if they had more sophisticated economic reasoning, these are the types of arguments they would make and they are the points brought up by the 2% of economists who don't care as much for free trade (e.g. Stiglitz). This is also ignoring the infant industries argument (favored by Rodrik), the national defence argument, or most arguments that point out that we may have more goals than efficiency and freedom (like food self-sufficiency). I'm also missing the anti-corporatist element and the more blatant self-serving protectionist arguments [made in particular by the corporatist element, right].

Now these aren't actually the arguments most people make. But if they had more sophisticated economic reasoning, these are the types of arguments they would make and they are the points brought up by the 2% of economists who don't care as much for free trade (e.g. Stiglitz). This is also ignoring the infant industries argument (favored by Rodrik), the national defence argument, or most arguments that point out that we may have more goals than efficiency and freedom (like food self-sufficiency). I'm also missing the anti-corporatist element and the more blatant self-serving protectionist arguments [made in particular by the corporatist element, right].